Threat Advisory: Browser Extension Spyware

Browser extensions are quietly exfiltrating AI data. UltraViolet TIDE analyzes how a popular VPN extension intercepts prompts and responses.

Find flaws in AI Systems

Find flaws in web, mobile, and IoT applications.

Expose risks in AWS, Azure, and GCP environments.

Ongoing testing to catch real-world vulnerabilities as they appear.

Live-fire exercises to sharpen detection and response.

Time-boxed security assessments across networks, apps, and infrastructure.

Simulated attacks to test detection and incident response.

Named security experts integrated seamlessly into your team.

Real-time detection and automated threat response.

24x7 monitoring and response by expert analysts.

Nonstop scanning to prioritize and reduce risk.

Ongoing scanning, triage, and compliance tracking.

Unified security platform powering all UV services.

Cross-platform toolkit for advanced red team ops.

Secure your code, infrastructure, and deployment pipelines before attackers exploit them.

Feb 3-5, 2026

Mar 19, 2026

Feb 19, 2026

UltraViolet Cyber is a practitioner-led MSSP delivering offensive and defensive security to Global 2000 and Federal clients. Built by former intelligence operators, we unify application security, red teaming, detection, and engineering under one roof. Our UV Lens platform replaces silos with integrated, outcome-driven operations.

UltraViolet Cyber

December 1, 2025

UltraViolet Cyber (UltraViolet) Threat Intelligence and Detection Engineering (TIDE) Team have worked closely with the UltraViolet Application Security Testing (AST) Network Security Team to uncover, analyze, and reverse engineer a novel social engineering and malware campaign directed at Red Team and Offensive Cybersecurity professionals. TIDE and AST Teams have dubbed this newly discovered campaign “AIRedScam”. This novel SmartLoader campaign closely follows the Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) of similar SmartLoader and Infostealer deployments, where a known technical search-engine topic is selected and then leveraged by an attacker through an official-looking Git repository to con junior to mid-skilled personnel into downloading and deploying malware. Normally, the search topics selected by threat actors running SmartLoader campaigns like this are surrounding Software License Cracks, Systems and Network Administration Automation Tasks, and Chat Service Bots. What sets AIRedScam apart is its choice in targeting Offensive Cybersecurity professionals looking for tools that can automate their enumeration and recon.

The “AIScan-N” tool, originally built by the Chinese Developer “SecNN” to provide a reverse Model Context Protocol (MCP) service, was repurposed by the threat actor running AIRedScam. “SecNN/AIScan-N” does appear to be suspicious due to its use of precompiled binaries and installation methods. However, “AIScan-N” was deemed out of scope for the purposes of this report.

This report covers initial discovery, social and business intelligence analysis, dynamic malware analysis, and solutions for enterprise environments to protect against this social engineering and malware threat moving forward. Please reach out to your UltraViolet Account Executive if you have questions or concerns about AIRedScam or need any clarification on the contents of the technical assessment.

SmartLoader is a modular, stealth-focused malware loader that surged in prevalence lately due to its flexible architecture, heavy use of LuaJIT scripting, and broad distribution across compromised GitHub repositories. Threat actors have increasingly used it as a delivery platform for high-value payloads—including RedLine, Rhadamanthys, Lumma, and other credential and data-theft tools—by embedding it within ostensibly legitimate utilities, gaming “mods,” and automation scripts. SmartLoader’s design allows it to perform extensive host reconnaissance, environmental checks, and staged execution before retrieving live payloads from attacker-controlled infrastructure. Its combination of obfuscation, evasive execution logic, and multi-stage Lua components makes it particularly difficult for traditional detection engines to analyze and classify at scale.

LuaJIT gives SmartLoader a powerful avenue for evading AV and EDR because it blurs the line between legitimate scripting and malicious execution while operating inside a highly dynamic runtime environment. Unlike traditional compiled malware, LuaJIT executes bytecode within an embedded Just-In-Time virtual machine, allowing malicious logic to be delivered in encrypted fragments, decoded in memory, and executed without ever writing a stable binary artifact to disk. This JIT-compiled execution model produces ephemeral machine code that changes across runs, undermining static signatures and reducing the usefulness of behavioral baselines built on repeatable opcode patterns. Additionally, LuaJIT’s foreign function interface (FFI) allows the script to call native Windows APIs directly—without spawning suspicious subprocesses—enabling reconnaissance, injection, and payload staging to occur inside what appears to be a benign scripting engine. The result is a loader that is far more difficult for endpoint tools to fingerprint, trace, or confidently classify, particularly when paired with SmartLoader’s environment checks and modular staging logic.

Throughout 2025, SmartLoader became a favored initial-access mechanism for both financially motivated groups and state-sponsored threat actors because its distribution pipeline and staging logic were easily adapted across multiple campaigns. The move toward supply-chain style seeding—particularly through GitHub projects, third-party mirrors, and SEO-driven lure content—expanded its reach into enterprise developer environments and administrative workstations. Detection complexity increased as adversaries continually refreshed repository control using burner identities, rotated delivery artifacts, and embedded SmartLoader into rapidly updated open-source project forks. For enterprise defenders, the threat now represents a persistent infiltration vector that blends code-repository abuse, malware-as-a-service payload delivery, and highly adaptive staging behavior, requiring tightened developer hygiene, enhanced repository provenance controls, and continuous validation of downloaded tooling across engineering and IT teams.

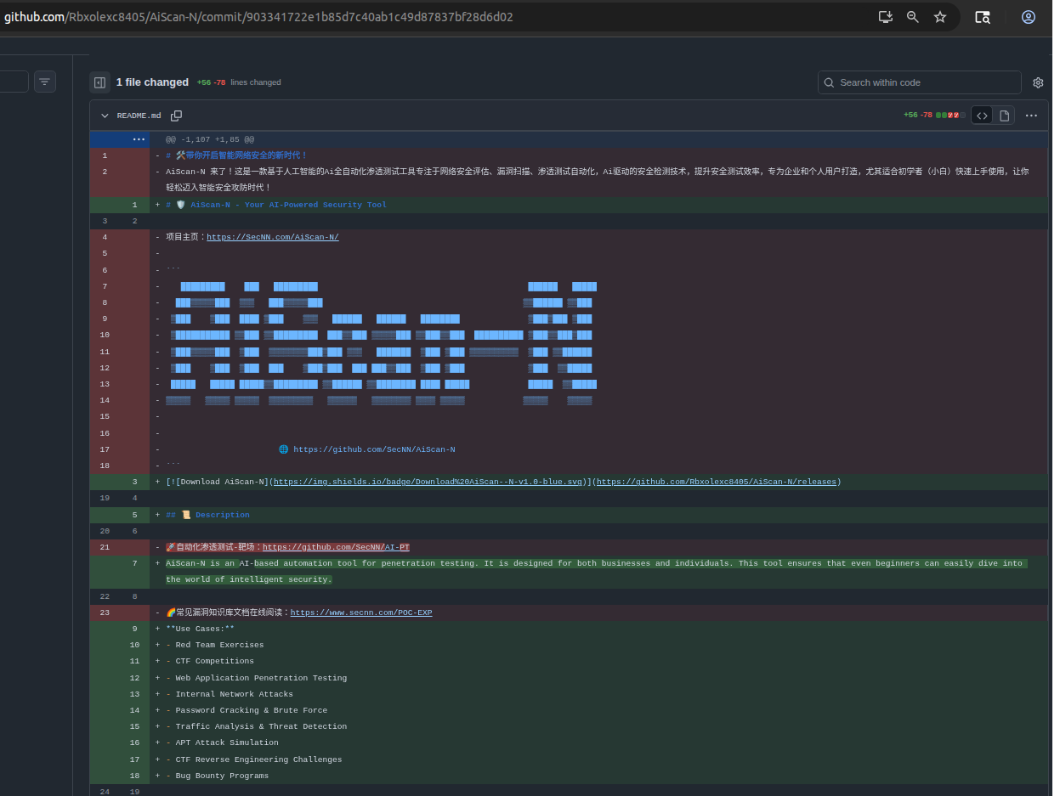

UltraViolet AST discovered the AIRedScam repository (https://github[.]com/Rbxolexc8405/AiScan-N) through their ongoing surveillance of the “AI Enabled Agentic Software Utilities” space. The offending repository was shared with the TIDE Team for further review. On November 21st, 2025, both teams came to a consensus that this was, in fact, a malicious GitHub repository due to the following traits:

The above screenshot shows the original and current SecNN/AIScan-N repository.

The above screenshot shows the original and current SecNN/AIScan-N repository.

The above screenshot demonstrates the original Chinese language README.md from the original SecNN/AIScan-N repo being repurposed to target English-speaking Offensive Cybersecurity personnel. Repository reuse through a fork, as demonstrated in the AIRedScam repository, is another hallmark of SmartLoader deployment and TTPs.

TIDE and AST Teams then downloaded the compressed malware archive and found four files inside. These files were:

Using a tightly controlled and custom sandbox environment, TIDE and AST teams further confirmed that this payload was a variant of SmartLoader. A Windows 10.0.19045 build was selected for the Sandbox VM. Upon manually executing Launcher.cmd the luajit.exe binary immediately copied itself into the “C:\users\%USERNAME%\AppData\Local\ODMw\” directory, along with the license.txt and lua51.dll files. Immediately after copying itself, the SmartLoader payload running inside of the JIT VM creates two scheduled tasks by leveraging WinAPI calls. This scheduled task creation creates persistence in the infected host.

The above redacted screenshot captures the “Setup” and “TaskScheduler_ODMw” scheduled tasks created by the initial detonation of the payload inside of the high interaction Sandbox. Also shown is the copied SmartLoader payload, with luajit.exe being renamed to ODMw.exe. TIDE and AST teams found that the four-letter pattern is common for the SmartLoader family, all in caps, except for the last character. This four-letter code is generated when the LuaJIT payload is generated by the threat actor and will be used to track future SmartLoader infections by UltraViolet TIDE and AST Teams and the UltraViolet Managed Detection and Response (MDR) Team.

The above redacted screenshot captures the “Setup” and “TaskScheduler_ODMw” scheduled tasks created by the initial detonation of the payload inside of the high interaction Sandbox. Also shown is the copied SmartLoader payload, with luajit.exe being renamed to ODMw.exe. TIDE and AST teams found that the four-letter pattern is common for the SmartLoader family, all in caps, except for the last character. This four-letter code is generated when the LuaJIT payload is generated by the threat actor and will be used to track future SmartLoader infections by UltraViolet TIDE and AST Teams and the UltraViolet Managed Detection and Response (MDR) Team.

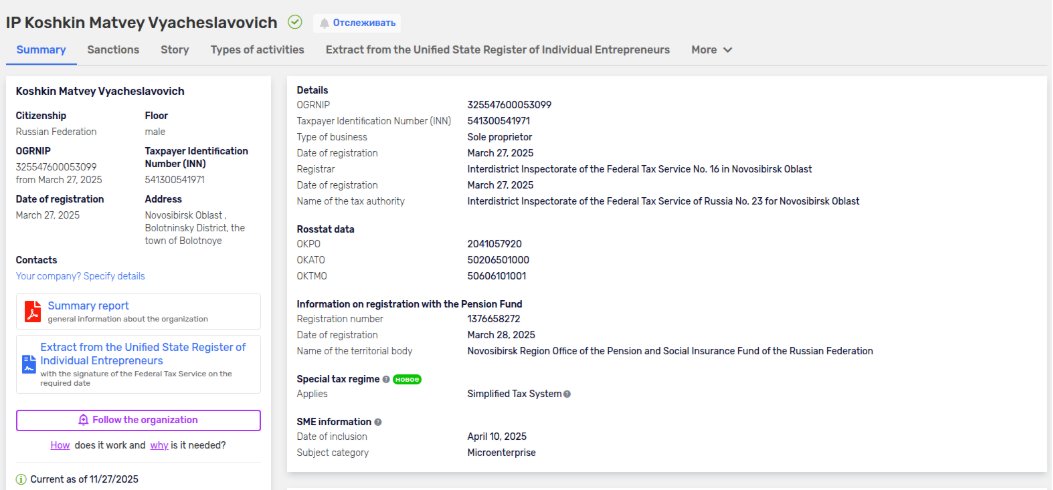

Alongside the Scheduled Task creation, a “Geo Fence” check is performed using the free “ip-api.com” service. This check ensures that the payload does not deploy and operate within the same country as the attacker. Then a series of plaintext HTTP requests were made to 85.209.129[.]236 on TCP/80. The 85.209.129.0/24 range is shown to be geographically located in Helsinki, Finland. The offending WAN IP is part of AS213702 as of November 2025. This ASN is owned by Qwins LTD, a Russian language Virtual Private Server (VPS) provider. Qwins LTD and the TIN/INN number listed on the website relate to a “Koshkin Matvey Vyacheslavovich” from Bolotnoye, Novosibirsk Oblast.

The Tax Payer ID Number (TIN) related to Koshkin Matvey Vyacheslavovich was established on March 27th, 2025. Other ASN ranges owned by QWINs were found to be geographically located in Germany, The Netherlands, Estonia, Poland, and the United Kingdom. These AS Ranges were all /24s, which are often used by state sponsored threat actors to quickly rearrange their WAN facing infrastructure to best suit their own national interests. The upstream provider for the offending ASN Range is AS209693, “OC Networks LTD”, a Russian owned VPS provider known to take Monero/XMR as payment.

The above screenshot is an automated translation of the TIN information found attributed to the owner of Qwins LTD.

The above screenshot provides GeoINT on the location of the offending WAN IP.

The above screenshot provides GeoINT on the location of the offending WAN IP.

The above redacted screenshot demonstrates the round trip HTTP plaintext request from ip-api.com/json/ back to the infect host with its own geographic information.

The above redacted screenshot demonstrates the round trip HTTP plaintext request from ip-api.com/json/ back to the infect host with its own geographic information.

The above screenshot shows similar malicious activity on the same range throughout 2025.

The above screenshot shows similar malicious activity on the same range throughout 2025.

After the Geo Fence request is complete, the LuaJIT payload takes a screenshot of the entire screen and then pushes the image as a Bitmap/BMP in a generic HTTP form-data block to the offending C2 API built on a VPS attacked to the Helsinki WAN IP. TIDE and AST Teams captured this traffic and were able to successfully unpack the BMP. This screenshot technique is common among all SmartLoader variants and is often used by attackers to look for desktop images, icons, taskbar icons and widgets, and other identifying indicators that could assist with precise targeting. Due to the LuaJIT payload firing every 24hours, a different payload could be selected by the attacker depending on the contents of the screen capture.

The above screenshot highlights a POST request form-data payload with a magic file number of “BM”. This is the start of a Bitmap/BMP payload that is being sent along with the POST Request.

The above screenshot highlights a POST request form-data payload with a magic file number of “BM”. This is the start of a Bitmap/BMP payload that is being sent along with the POST Request.

The above screenshot demonstrates binwalk being used to extract the BMP payload from the captured raw HTTP frame. On the top is the binwalk extraction, on the bottom is the “EC” file being opened in an image viewer, which shows the Win10 sandbox screencapture from the LuaJIT payload.

The above screenshot demonstrates binwalk being used to extract the BMP payload from the captured raw HTTP frame. On the top is the binwalk extraction, on the bottom is the “EC” file being opened in an image viewer, which shows the Win10 sandbox screencapture from the LuaJIT payload.

After the screen capture was sent, the offending API responded with a JSON payload. This activity also closely matches other known SmartLoader variants.

The above screenshot shows the entire JSON response from the offending API.

The above screenshot shows the entire JSON response from the offending API.

Instead of tackling the payload obfuscation and encryption directly, TIDE and AST Teams decided to rely on additional network traffic monitoring to understand what the offending Russia-Nexus C2 API was sending to the sandbox victim. While TIDE and AST Teams are actively performing static malware analysis on the provided artifacts, it was deemed more important to observe the infection chain holistically and dynamically instead.

After the Geo Fence check and initial C2 API requests were made, the LuaJIT payload resolved and accessed two additional GitHub-hosted files:

Both GitHub accounts were created in November 2025 and have a single repository. This is a clear indicator of a “burner account”, meaning that the actor behind the account is treating it as a disposable asset.

The above screenshot is one of the offending GitHub malware hosts. The Venkatesan-M4 account mentioned previously was created on November 16.

The above screenshot is one of the offending GitHub malware hosts. The Venkatesan-M4 account mentioned previously was created on November 16.

The above screenshot demonstrates the README.md being clearly AI/LLM-generated. Each of the links in the README.md points to files.com, a legitimate organization in Tempe, Arizona, US.

The above screenshot demonstrates the README.md being clearly AI/LLM-generated. Each of the links in the README.md points to files.com, a legitimate organization in Tempe, Arizona, US.

TIDE and AST Teams analyzed both of the files hosted in the offending GitHub accounts and once again found heavily obfuscated and encrypted payloads. OSINT collection was performed on the GitHub usernames, but nothing was found on either that relates to Malware Development or Russian-Nexus actors; both usernames and profile names appear randomly generated.

The above screenshot shows the “numeric.txt” and “update.log” obfuscated files being downloaded by LuaJIT from GitHub and written into the “%APPDATA%\Local\Temp” directory as “socket.lua” and “stdlib.lua” respectively. Interestingly, the Socket2.The lua file was the raw HTML of the GitHub 404 page, which points to further misconfiguration in this SmartLoader payload.

The above screenshot shows the “numeric.txt” and “update.log” obfuscated files being downloaded by LuaJIT from GitHub and written into the “%APPDATA%\Local\Temp” directory as “socket.lua” and “stdlib.lua” respectively. Interestingly, the Socket2.The lua file was the raw HTML of the GitHub 404 page, which points to further misconfiguration in this SmartLoader payload.

The above screenshot demonstrates the LuaJIT binary payload checking registry keys that control system settings. It also looked for Image File Execution Options (IFEO) on itself, as that can often be a sign of reverse engineering or analysis.

The above screenshot demonstrates the LuaJIT binary payload checking registry keys that control system settings. It also looked for Image File Execution Options (IFEO) on itself, as that can often be a sign of reverse engineering or analysis.

TIDE and AST Teams monitored the sandbox environment with the live LuaJIT payload and scheduled tasks for over 24hours. No additional C2 API callouts were made, and subsequent normally fired scheduled tasks performed the same steps. This lack of additional activity could be due to numerous reasons:

As of November 27, 2025, TIDE and AST Teams have collected enough intelligence from this campaign to design bespoke detections to protect UltraViolet customers and partners. TIDE and AST will continue to explore and analyze the AIRedScam campaign and will update this report if new and useful intelligence is collected.

The AIRedScam campaign is unique in its targeting of Red Team and Offensive professionals looking to automate their recon and enumeration stages during an engagement. However, AIRedScam is very average from a technical standpoint. The use of LuaJIT, the file names, the payload behavior, and the host targeting are almost identical to all other SmartLoader campaigns that have popped up throughout 2025. The AIRedScam payload, and similar SmartLoader payloads, are stealthy and rarely trigger Windows Defender and other AV/EDR products. Registry object checks and anti-reversing techniques are all aligned with standard SmartLoader behavior as well.

While the offending C2 API WAN IP is hosted out of a Russia-Nexus-owned ASN Range, this does not necessarily mean that the threat actor behind the AIRedScam campaign was associated with Russian state interests, especially with Geo Fence checks failing when presented with a geographically Russian WAN POP IP on the victim sandbox. As we have seen throughout the last decade, Threat Actors often maintain excellent OPSEC and FINSEC, which makes them extremely hard to enumerate and hunt individually. This adherence to OPSEC and FINSEC fundamentals is seen in the AIRedScam campaign through the use of burner accounts and the use of VPS providers in a non-FVEY country that can accept “bullet-proof” payment options.

From a technical standpoint, the AIRedScam payload and subsequent malware it pulls down from burner GitHub accounts are nothing more than a carbon copy of similar SmartLoader malware. What sets AIRedScam apart is its choice of human targeting. This campaign preys upon junior to mid-skilled Red Team Operators looking to automate their workflows, individuals interested in Offensive Capture the Flag, and curious SysAdmins. UltraViolet TIDE and AST teams believe this is just the start of a new trend of targeting the Offensive Cybersecurity community, not only with supply chain attacks against commonly used offensive tools, but also targeting the emergent need to automate and augment offensive workflows with AI/LLM-backed infrastructure. UltraViolet TIDE and AST Teams urge extreme caution when downloading and executing precompiled binaries and compressed archives from any source online, no matter how good the README.md appears.

Enterprise environments can reduce their exposure to SmartLoader by strengthening software provenance controls and narrowing the attack surface created by unmanaged code acquisition. Because SmartLoader spreads primarily through compromised GitHub repositories, fake tooling, and SEO-driven lure content, organizations should enforce strict policies around how administrators, developers, and engineers obtain utilities and scripts. Centralized software repositories, controlled package mirrors, and mandatory code-signing validation dramatically limit the risk of inadvertently introducing malicious loaders through routine workflow automation. Combined with browser isolation or application sandboxing for high-risk download activities, these controls prevent SmartLoader from exploiting open-source trust relationships and developer supply-chain habits.

Defense-in-depth across the endpoint is equally important, particularly because SmartLoader’s LuaJIT architecture is difficult for traditional controls to classify. Enterprises should deploy EDR controls capable of monitoring script engines, foreign function interfaces, unusual in-memory JIT activity, and anomalous network beacons originating from nonstandard interpreters. Memory scanning, AMSI enhancement, and heuristic detection of dynamic call chains can help identify SmartLoader’s staged execution even when the loader itself is obfuscated. Additionally, enforcing application allow-listing and restricting the execution of unsigned or unpackaged interpreters reduces the ability of SmartLoader to escalate from an initial Lua script to a fully functional staging platform.

Finally, organizations must treat SmartLoader as a broader supply-chain and developer-workflow threat, not merely a malware sample. Security teams should integrate repository validation, dependency checks, and real-time monitoring of cloned open-source projects into CI/CD pipelines to prevent poisoned artifacts from entering development ecosystems. Regular red-team exercises focused on GitHub impersonation, malicious tool repositories, and drive-by administrative tooling downloads can uncover blind spots in procurement and developer hygiene. By combining technical controls with cultural and process-oriented changes—such as mandatory training for engineers on source authenticity and tooling security—enterprises can significantly reduce the likelihood that SmartLoader infiltrates their environment and weaponizes trusted workflows.

UltraViolet TIDE and AST Teams suggest heavily restricting LuaJIT within your environment if there is no official business need for this software.

|

https://github[.]com/Rbxolexc8405/AiScan-N/ |

|

https://github[.]com/Rbxolexc8405/AiScan-N/blob/main/cteniform/AiScan-N-v2.4.zip |

|

https://github[.]com/Venkatesan-M4/file_storage |

|

https://raw.githubusercontent[.]com/Venkatesan-M4/file_storage/refs/heads/main/numeric.txt |

|

https://github[.]com/nluffer/update |

|

https://raw.githubusercontent[.]com/nluffer/update/240040191eb5b30c2074655bc26be94ab03d8559/update.log |

|

b22dd8f01257d692b7a6d731a05a1a958596a2cb1844bafdfa339581cd7f57f8 |

|

4a37905fc01a4316507ec4f88b3b0aa8ee5f6afae2f85f77e48acd1923bf5eed |

|

c3d1d08d383f5346febd9280e6796baa2208c5136bb7c3f66645b303f74d531f |

|

0575bb1a77b956d6eac6c6aa7dfb53e611e8b52955436e6e73c0e802bfa23dba |

|

fc88eaff5fea14f3aedc1bf6a4d147ee56b6b466c85fd0b17248a3a7ecd60c6f |

|

5343326fb0b4f79c32276f08ffcc36bd88cde23aa19962bd1e8d8b80f5d33953 |

|

c7a657af5455812fb215a8888b7e3fd8fa1ba27672a3ed9021eb6004eff271ac |

|

85.209.129[.]236 |

|

http[:]//85.209.129[.]236/api/ |

|

93.123.39[.]74 |

|

http[:]//93.123.39[.]74/api/ |

|

AS209693 - OC Networks LTD |

|

AS213702 - Qwins LTD |

We’re here to help. Get in touch for an initial conversation with one of our security experts and learn more about how UltraViolet Cyber can help you take cyber readiness and resilience to new levels.